Pōhaku, Kalo, Wai: Stewardship

in Contemporary Hawai’i

Lower Limahuli Preserve, Ha’ena, Kaua’i

Work: Geospatial data acquisition, visualization, and conservation planning for a historic water system complex

Scale: 2.8 ac

Completion: (in fundraising) 2023

Description:

A journey through time and landscape uncovers an ancient agricultural heritage hidden beneath the overgrowth. This project, born from three years of on-site schematic spatial research, seeks to revive an indigenous agroecological system within Limahuli Valley. Its focus, a prehistoric 2.8-acre terraced agricultural homestead located adjacent to active restoration work taking place within the Preserve today. This project explores the site as a catalyst for the revival and integration of cultural heritage landscapes into forestry conservation planning.

Lower Limahuli Preserve, Ha’ena, Kaua’i

Work: Geospatial data acquisition, visualization, and conservation planning for a historic water system complex

Scale: 2.8 ac

Completion: (in fundraising) 2023

Description:

A journey through time and landscape uncovers an ancient agricultural heritage hidden beneath the overgrowth. This project, born from three years of on-site schematic spatial research, seeks to revive an indigenous agroecological system within Limahuli Valley. Its focus, a prehistoric 2.8-acre terraced agricultural homestead located adjacent to active restoration work taking place within the Preserve today. This project explores the site as a catalyst for the revival and integration of cultural heritage landscapes into forestry conservation planning.

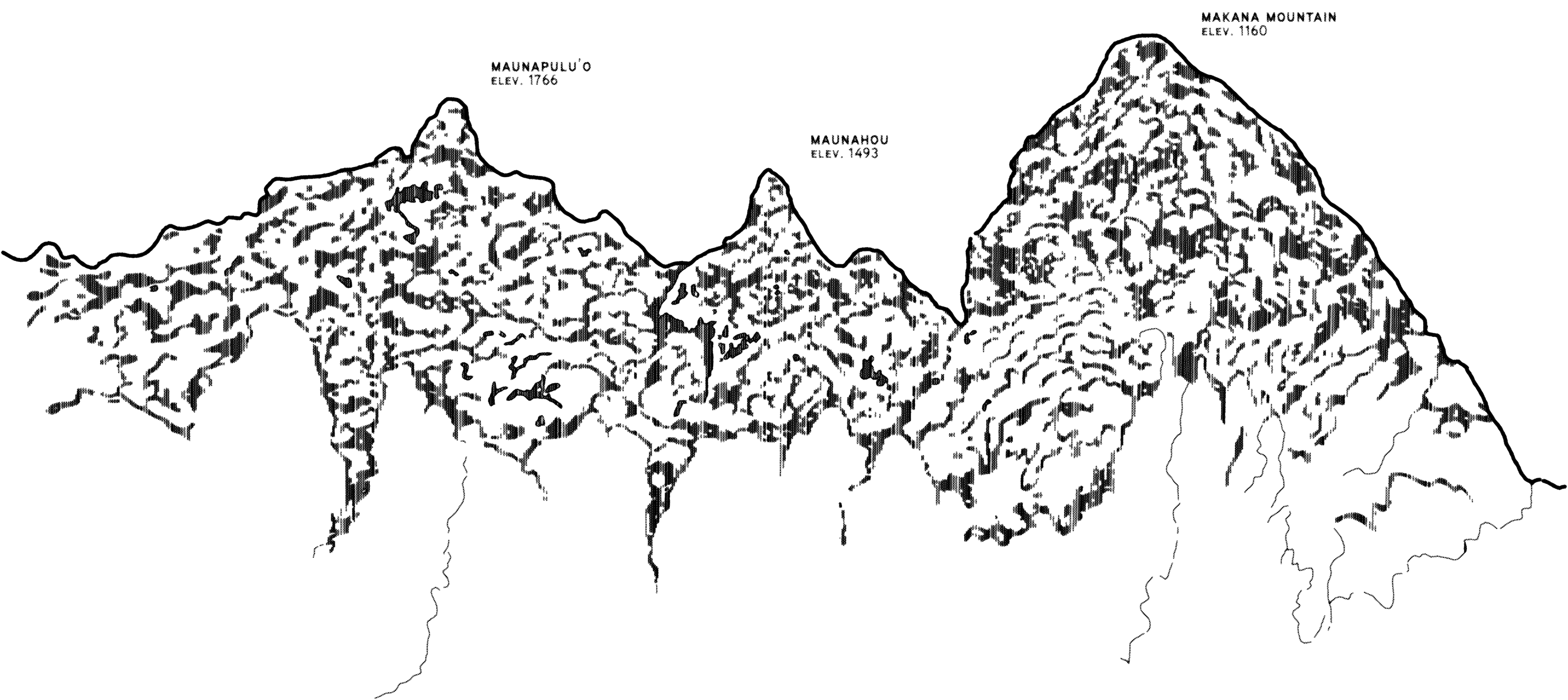

Here, in

Limahuli Valley, the mountains rise above the clouds, as if only tethered down

to earth by the roots and vines of a 20th century momentum in the landscape.

Their black volcanic faces gaze out over the expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

Carved from basalt, they stand as ancient warriors engaged as protectors, their

forms so abstract and muscular, it’s as if they were only shaped and chiseled

by some wild surrealistic kind of deity. Here, in Limahuli Valley, the pōhaku

(stones) have names, stories, histories, characteristics as distinct as you or

I.

Like a sculptor hammering away at raw mass, the valley floor is populated by the stones fallen from the valley walls. What crumbles down, joins the boulder fields below. Rainwater from the Wao Akua (cloud forest) feeds the stream. Its flow braids its way through the low points in the valley’s bottom, splitting the valley into near perfect halves, an east and west. Today, Lower Limahuli Preserve encompasses the 600-acre lower valley. To navigate the valley, beyond the boundary limits of the Garden, imagination is perhaps your most essential companion.

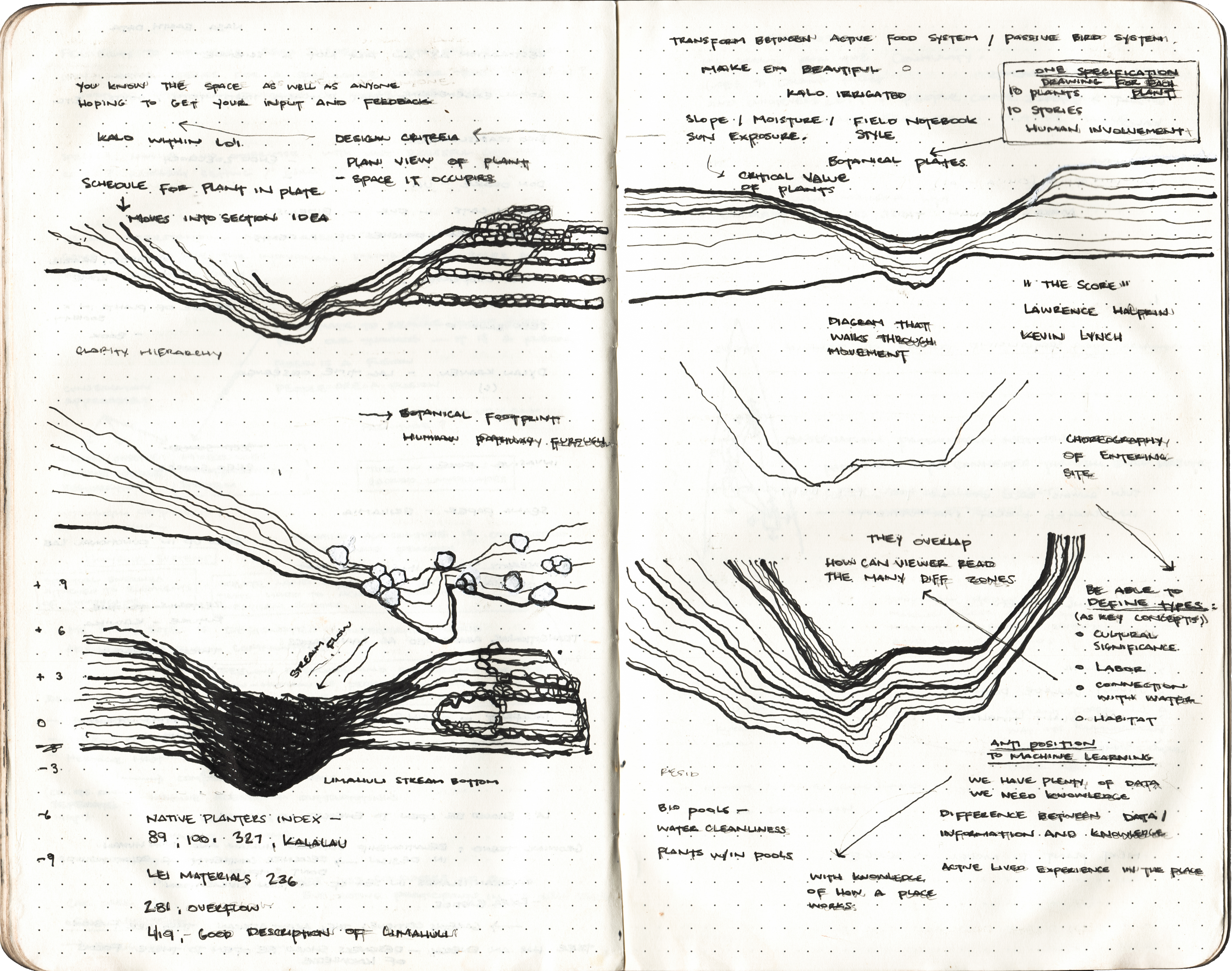

I began my work as a field technician in the Preserve. Uncovering the valley’s rich history and enduring traditional practices propelled me towards my graduate studies in landscape architecture at Harvard University. What began as a series of inquisitive sketches of these ancient walls, evolved into three years of research for my design thesis. The objective was to uncover the archaeological framework of an indigenous agroecological system within Limahuli Valley, exploring how the system can be revitalized and incorporated into broader restoration efforts to exemplify a new standard of biocultural conservation. This project presents a vision for reinterpreting the valley’s legacy through its stonework.

Like a sculptor hammering away at raw mass, the valley floor is populated by the stones fallen from the valley walls. What crumbles down, joins the boulder fields below. Rainwater from the Wao Akua (cloud forest) feeds the stream. Its flow braids its way through the low points in the valley’s bottom, splitting the valley into near perfect halves, an east and west. Today, Lower Limahuli Preserve encompasses the 600-acre lower valley. To navigate the valley, beyond the boundary limits of the Garden, imagination is perhaps your most essential companion.

I began my work as a field technician in the Preserve. Uncovering the valley’s rich history and enduring traditional practices propelled me towards my graduate studies in landscape architecture at Harvard University. What began as a series of inquisitive sketches of these ancient walls, evolved into three years of research for my design thesis. The objective was to uncover the archaeological framework of an indigenous agroecological system within Limahuli Valley, exploring how the system can be revitalized and incorporated into broader restoration efforts to exemplify a new standard of biocultural conservation. This project presents a vision for reinterpreting the valley’s legacy through its stonework.

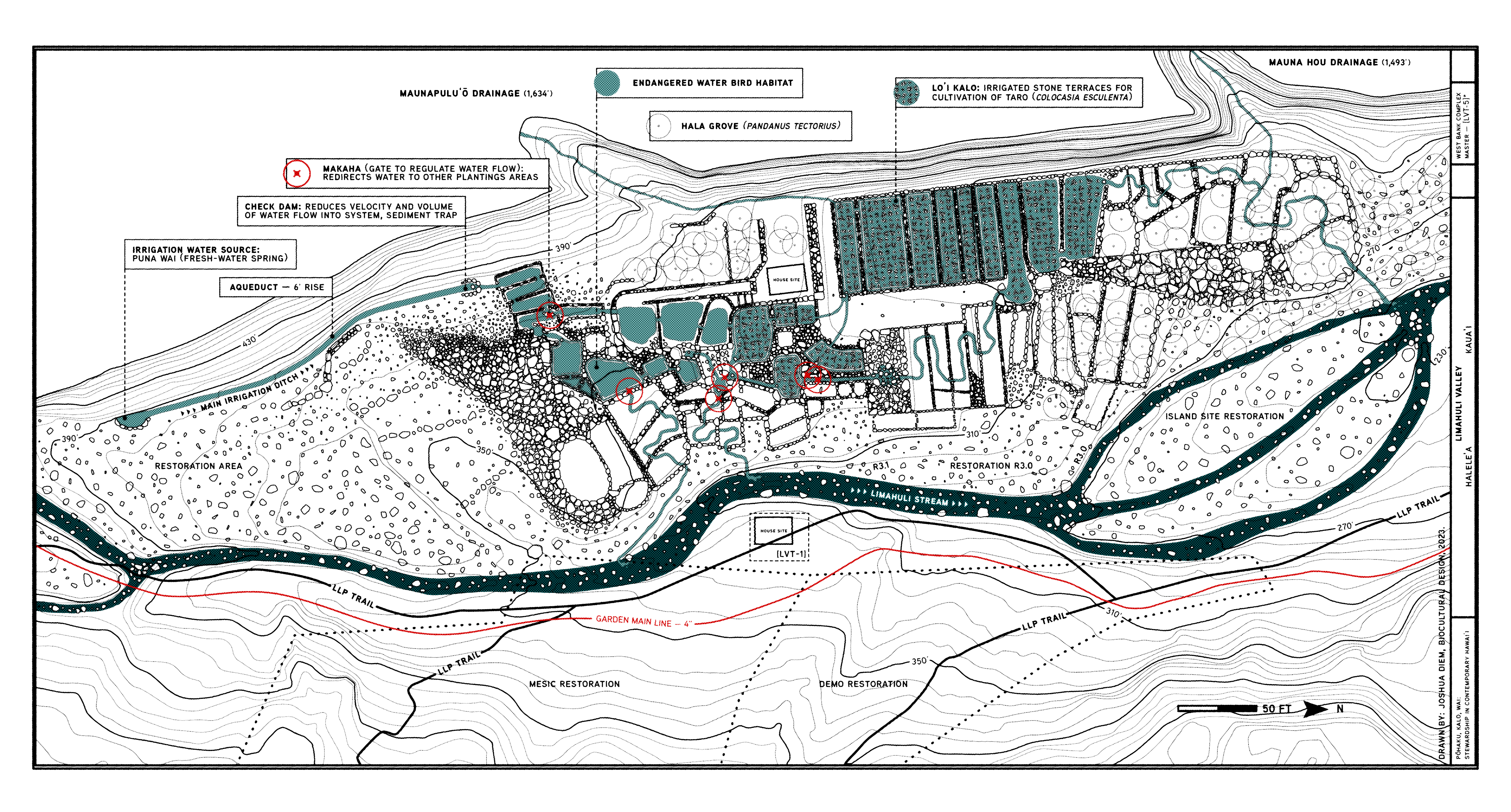

The site of my research is the 2.8 acre

ʻilipaʻa (agricultural homestead) built several centuries ago between the

Limahuli Stream and the valley’s western wall. Standing below Mauna Hou and

Maunapuluʻō peaks, the site includes over one hundred interconnected loʻi

(stone terraces) once used for irrigating kalo (taro).

The primary house site, positioned at the compound’s midpoint, allowed its inhabitants to oversee water management and crop rotation. Assuming wetland crop yield was comparable to today, this agricultural system may have sustained a family unit of approximately 20-50 members. We are uncertain of the identity of the ʻohana (family) who once inhabited and nurtured the site or how they or their ancestors moved the stones. Whoever fed from this place, cared for the source of its wai (fresh water).

![]()

The primary house site, positioned at the compound’s midpoint, allowed its inhabitants to oversee water management and crop rotation. Assuming wetland crop yield was comparable to today, this agricultural system may have sustained a family unit of approximately 20-50 members. We are uncertain of the identity of the ʻohana (family) who once inhabited and nurtured the site or how they or their ancestors moved the stones. Whoever fed from this place, cared for the source of its wai (fresh water).

Today, overgrown

neke fern swamp hides the existence of the puna wai (fresh-water spring) that continues

to seep from an opening in the valley wall. Channeled into the ʻauwai puhi

(main irrigation ditch), gravity directs the flow of water, initially tracing

its line along the base of the pali (cliff). The ditch crosses a small aqueduct-like

structure and pools in a check dam. Finally, the water is distributed into the

loʻi kalo. When

this landscape was actively cultivated, it must have evoked a profound sense of

rhythm and connection.

This ʻilipaʻa was likely inhabited until the mid-19th century when its abrupt abandonment may have been the result of sweeping changes in property tax laws throughout the Hawaiian Kingdom. These policies reflected the broader social, political, and economic changes in Hawai‘i during that time and left the valley without its stewards.

Walking into the Limahuli Preserve is like traveling through time. Step off the trail and you risk getting lost in a dense tangle of vegetation. Although difficult to discern to the unfamiliar eye, the landscape is a dynamic expression of the interplay between people and their environment with remains of the terraces, irrigation channels, and house sites. Garden plots that once flourished now lie overgrown and hard to recognize.

To recover these ruins, the site was surveyed and validated using GPS and Lidar instrumentation. The collected data was then integrated into architectural design software to build models of the site.

This ʻilipaʻa was likely inhabited until the mid-19th century when its abrupt abandonment may have been the result of sweeping changes in property tax laws throughout the Hawaiian Kingdom. These policies reflected the broader social, political, and economic changes in Hawai‘i during that time and left the valley without its stewards.

Walking into the Limahuli Preserve is like traveling through time. Step off the trail and you risk getting lost in a dense tangle of vegetation. Although difficult to discern to the unfamiliar eye, the landscape is a dynamic expression of the interplay between people and their environment with remains of the terraces, irrigation channels, and house sites. Garden plots that once flourished now lie overgrown and hard to recognize.

To recover these ruins, the site was surveyed and validated using GPS and Lidar instrumentation. The collected data was then integrated into architectural design software to build models of the site.

The valley’s

landscape is a complex tapestry of social, cultural, and ecological narratives

that make up the ahupuaʻa system of resource management. This centuries-old

traditional land division, often similar to the shape of a watershed, allowed

Hawaiians to organize and sustain resources through planning,

interconnectedness, and cultural values.

Over time, my ability to discern the role of stone within this valley’s ahupua’a system was refined under the guidance of my mentors and colleagues, Moku Chandler and Noah Kaʻaumoana, both stewards of Limahuli Valley and masters of traditional stone craftsmanship. Through their mentorship, stone has revealed itself. Ancient architecture seemed to emerge naturally from the earth, unveiling its framework and function.

![figure.]()

Over time, my ability to discern the role of stone within this valley’s ahupua’a system was refined under the guidance of my mentors and colleagues, Moku Chandler and Noah Kaʻaumoana, both stewards of Limahuli Valley and masters of traditional stone craftsmanship. Through their mentorship, stone has revealed itself. Ancient architecture seemed to emerge naturally from the earth, unveiling its framework and function.

It is not merely

the ruins themselves that have captivated me, but rather their spatial

relationship with the land’s physical form. There exists a profound sense of

alignment, where the landscape became a canvas configured of stone walls,

patterns, and symmetries, constructing a narrative that can be read like

braille.

The first Polynesians who arrived here had to adapt to a range of environments, building agricultural systems that mirrored the natural processes and features of each ecosystem. For a river valley like Limahuli, land suitable for growing kalo was typically found in alluvial flood plains adjacent to the stream. By manipulating the water flow in these plains, wetland kalo became the central crop of the early Hawaiians and a symbol of the kinship between humans and the land. The intuitive natural design of these irrigation systems was the result of generations of cumulative knowledge, tailored to the distinctive characteristics of each environment and the creative choices made by the makaʻāinana (people who tended the land).

The first Polynesians who arrived here had to adapt to a range of environments, building agricultural systems that mirrored the natural processes and features of each ecosystem. For a river valley like Limahuli, land suitable for growing kalo was typically found in alluvial flood plains adjacent to the stream. By manipulating the water flow in these plains, wetland kalo became the central crop of the early Hawaiians and a symbol of the kinship between humans and the land. The intuitive natural design of these irrigation systems was the result of generations of cumulative knowledge, tailored to the distinctive characteristics of each environment and the creative choices made by the makaʻāinana (people who tended the land).

Today, one of the

primary objectives of NTBG’s work in the Limahuli Preserve is to restore native

forest. But the archaeological clues that remain in the landscape should not be

overlooked. As a landscape architect, I think beyond the ecologic functionality

of a place to also consider its beauty, stories, and human-introduced qualities. Working in the valley, I have filled my field notebooks with architectural

illustrations, documenting my observations and understanding of how this

landscape functioned in an earlier time. By retracing the genius in the

placement of the stones, we can recover a framework from when this site was an

integrated forest where agriculture thrived.

This ʻilipaʻa site holds great promise for restoration. Much of the invasive understory that has engulfed the valley floor has yet to encroach and many of the rock walls remain intact. The source of irrigation water still flows and, importantly, the site falls within the active restoration zone of the Lower Limahuli Preserve, accessible by a short hike.

This ʻilipaʻa site holds great promise for restoration. Much of the invasive understory that has engulfed the valley floor has yet to encroach and many of the rock walls remain intact. The source of irrigation water still flows and, importantly, the site falls within the active restoration zone of the Lower Limahuli Preserve, accessible by a short hike.

The loʻi terraces

serve as the foundational architecture that informs the restoration process.

Through the strategic and phased removal of invasive canopy trees and the

excavation of the ‘auwai, water can flow back into the landscape. Native

restoration plantings can be interwoven into the water system to create a novel

landscape that embodies biocultural conservation.

The integration of this historical agricultural system has the potential to serve as a haven for endangered water birds, nourish restoration plantings during periods of drought, and utilize natural drainage to improve soil fertility. Furthermore, the reintroduction of traditional farming practices and passive food production is significant as an expression of the community’s most cherished values and highest aspirations.

The integration of this historical agricultural system has the potential to serve as a haven for endangered water birds, nourish restoration plantings during periods of drought, and utilize natural drainage to improve soil fertility. Furthermore, the reintroduction of traditional farming practices and passive food production is significant as an expression of the community’s most cherished values and highest aspirations.

As we strive to restore

native forest, it is important that we help perpetuate the agricultural legacy

surrounding us. Throughout Hawaiʻi, other sites of great cultural heritage

exist on conservation lands, waiting to be rediscovered and revitalized.

Limahuli Valley can serve as a model for a new integrated approach to

stewarding Hawaiʻi’s future in a way that builds bridges between the humanities

and science.

Featured In: